In early December 2020, Governor Kelly’s Commission on Racial Equity and Justice released its initial report on “Policing and Law Enforcement in Kansas.” The report contained some solid recommendations aimed at improving law enforcement interactions with the communities they are sworn to protect.

But if Governor Kelly really wants to take actionable steps to address systemic racism in our criminal-legal system, then the report’s recommendations must be viewed as the floor rather than the ceiling.

The Report’s recommendations center on themes common in police-reform discussions: better training for officers; more transparency into police actions and discipline; enhanced accountability, including improving complaint processes and access to data; and improving officer recruitment and retention practices.

These are good ideas, at least in the abstract. But they are also the bare minimum.

We should already ensure that officers are properly trained. There should already be robust mechanisms for community members to have an avenue to complain about police misconduct. To the extent that body-worn cameras are already in use, their deployment should be governed by “evidence-based practices.”

Perhaps most shocking is the recommendation that officers complete firearm training before they are issued a firearm to use in the line of duty. Yet many agencies statewide do not yet follow these (and more) basic requirements. Perhaps the Commission had no choice but to include these as recommendations for future action.

Other recommendations highlight the need for changes intended to improve police-community interactions, but may not have the desired effect. For example, many recommendations center on improving diversity in hiring and promotion, with the goal of having law enforcement command structures and police ranks look more like the communities they police. Other recommendations call for anti-bias training.

Although this sounds nice, such trainings do little to stop the type of brutality on display with the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor this summer. As researchers and advocates have pointed out, police brutality will not be solved by increased officer diversity or one-off anti-bias or procedural justice trainings.2

In 2015, the Minneapolis Police Department budgeted $300,000 for anti-bias training for its officers,3 but Derek Chauvin still killed George Floyd, kneeling on Floyd’s neck until Floyd’s one, last, desperate breath.

Many of the Commission’s recommendations also fall short of the benchmarks contained in President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. That report – released over five years ago—came in response to a flood of uprisings in the wake of the murder of Michael Brown by Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson. The Task Force’s report also focused on transparency and accountability, including building trust between police and communities, improving training, and increasing oversight.

The Task Force recommendations led to changes in police policy and practice in many jurisdictions, and is often cited as a guide for best practices in law enforcement.

The KCREJ’s recommendations, however, although similar in some respects, also fail to encompass some of the most important aspects of the Task Force’s report. The Commission’s report, for example, contains very few recommendations regarding use of force. The Task Force specifically calls for officers to de-escalate situations and utilize alternatives to arrest;4 the Commission’s recommendations do not.

Today, we could argue that even the 21st Century Policing Task Force’s recommendations are not enough. We have learned more about the effectiveness of these reforms in the years since. The conversation has changed—especially after mass protests this summer and widespread calls to defund the police. We should be thinking more critically about how police are used throughout the state, and what services or supports may be better positioned to intervene in certain situations than armed law enforcement. We should be looking at ways to shrink the power and purpose of police, and therefore reduce the number of potentially harmful contacts between police and Black and Brown communities.

The Commission’s recommendations do not touch on this. There are several recommendations regarding how law enforcement agencies can increase their funding streams, but no recommendations—at least in this report--to Governor Kelly or the legislature regarding investing in better medical and mental healthcare for struggling communities, or fund restorative justice programming or other non-carceral interventions for the many social problems that police are called in to address. Those were the demands of racial justice activists this past summer, and they are not found in many of the Commission’s recommendations. Instead, the Commission pushes for crises response units within law enforcement; that mental health workers “ride with and work alongside law enforcement” and that law enforcement officers receive more training on mental health crisis response. These recommendations may provide interim fixes but do not address the underlying problem of a lack of services and supports within the community, or the outsized and problematic role law enforcement plays in responding to crises.

There are some important recommendations that will pave the way for future action.

Recommendation DAT.3, to implement a state-wide data collection program for pull over and stop data will greatly increase access to information that is necessary to ensure officers are not targeting racial minorities or engaging in policing without the requisite level of suspicion or probable cause. In our current litigation against the Kansas Highway Patrol, where we allege targeting of drivers based on their out-of-state license plates and/or travel plans, this type of data would be invaluable. We also sincerely hope that the Commission’s recommendation to “study and assess” technical probation violations leads to concrete actions. We already know from Kansas Sentencing Commission data that a large number of people in our state’s prisons and jails are there for non-criminal violations of the terms of their probation or parole. Legislative and executive policy fixes to how law enforcement agencies handle probation violations are long overdue.

Likewise the Commission’s recommendations regarding public defense, school resource officers, and more stringent screening of prospective officers may also decrease the number or severity of criminal-legal system contacts. The recognition of problems attendant to law enforcement interaction with immigrant and tribal communities is also meaningful. Putting these recommendations into action will hopefully push us to get police out of schools and reduce the school to prison pipeline; bolster support for sanctuary communities; and ensure that tribal lands and communities are respected and free from police brutality.

The Commission’s report gives us a lot to think about. In some ways, it is a blueprint for where the bipartisan, highly qualified members of the Commission view the current state of policing in Kansas.

It seems clear, however, that presumed resistance from the Legislature’s Republican super majority lowered the Commission’s sites, leading to the Commission settling for at best, modest reforms. This really should surprise no one. Such Commissions rarely produce sweeping changes. Rather, they are the places where the most thoughtful and progressive ideas are laid to rest.

But as we think about the ways to make good on Governor Kelly’s desire to “make fundamental changes to how police interact with the communities they are empowered to protect,” we should consider this document as a baseline. A good place to start.

Bolder, transformational change is urgently necessary and possible. We certainly have not been timid about running roughshod over people’s rights, we should not be timid about acknowledging those wrongs and fixing them.

Sharon Brett, Interim Legal Director at the ACLU of Kansas

Sharon Brett is Interim Legal Director at the ACLU of Kansas. Prior to joining the ACLU, Sharon was a Senior Staff Attorney at the Criminal Justice Policy Program (CJPP) at Harvard Law School, where conducted policy research and advocacy related to the criminal legal system.

1 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1541-0072.t01-1-00009?de...

2 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/30/opinion/george-floyd-police-funding.html ; https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/08/opinion/george-floyd-protests-race.html;

3 https://www.mprnews.org/story/2015/12/10/mpls-police-bias-training

4 https://cops.usdoj.gov/pdf/taskforce/taskforce_finalreport.pdf

Date

Friday, January 15, 2021 - 3:30pm

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Override default banner image

Related issues

Criminal Legal Reform

Show related content

Pinned related content

Clemency Q&A with Sharon Brett, Legal Director

The Women Left Behind

During today’s historic release, we remember the power of homecoming

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Show PDF in viewer on page

Style

Standard with sidebar

Show list numbers

If you passed me on the street, you wouldn’t assume I was an ex-convict. In fact, once people get to know me, and find out I spent almost six years in prison, they are shocked. I often hear “you don’t look like someone who has been to prison!” In many ways, that’s reassuring, but begs the question, “what do people who have been to prison generally look like?”

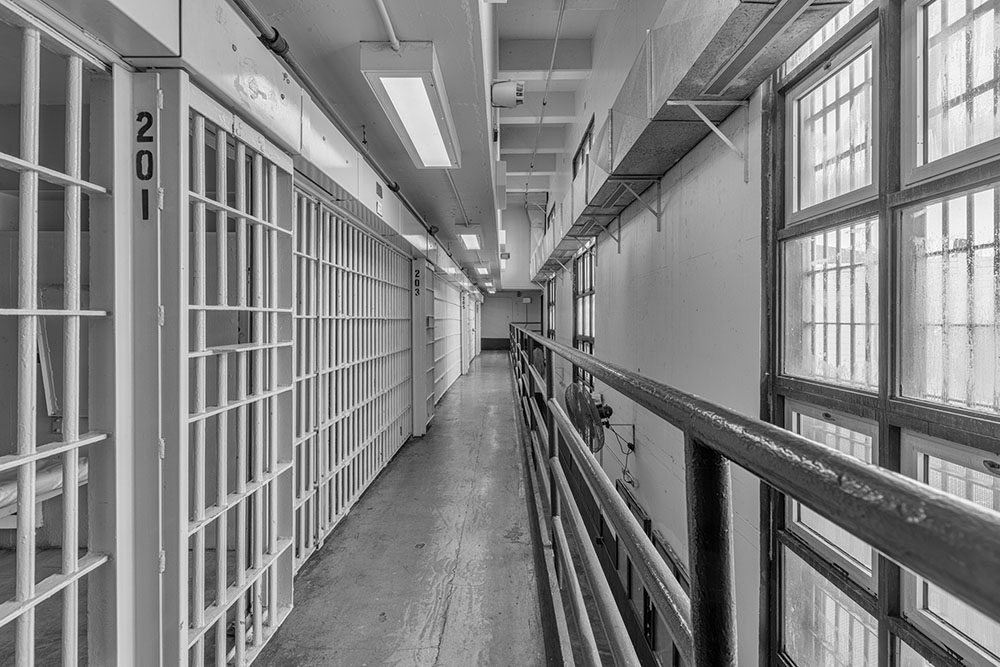

I was 17 years old when my involvement in a homicide resulted in a 5-to-20-year prison sentence. I remember acutely being a new inmate in March of 1992 and walking down what we called the cattle chute. The yard was on the left and a crowd of inmates were heading back to their cells. I looked up at the three-story high cell houses and thought to myself “this is it, bottom of the barrel.”

It was in that moment that a slow fire began to burn and I vowed then and there to do whatever was necessary to change myself and to make sure upon release I would never return. I finished my GED, took college courses, completed drug and alcohol treatment and continued with 12-Step meetings. I received certificates in welding, and tried to take advantage of every self-help program or group available.

It was through an organization called Reaching Out from Within (ROFW) that I truly emerged from the protective shell I had created. ROFW helped me begin the deep, introspective search necessary to understand why I had done the things I had done and what I still needed to do to change. This organization also helped to connect me with other inmates who were on a similar path.

The welding training led to a job while I was still in prison and after my release I continued working as a welder, attending 12-Step meetings, and keeping my nose clean. I spent two years on parole before being released. In July of 2011, I was able to get my record expunged.

My goal of giving back came to fruition in November of that same year when I was permitted to return to prison, no longer as an inmate but, rather, as a volunteer and mentor.

Looking back with the benefit of time, I realize that not everyone has the same experiences in prison and the results aren’t always as positive for others as they were for me, and we need to ask the tough question, “why?”

Why does our system work better for some than for others? Why are opportunities more plentiful for people like me who looked like me, a typical white kid from the suburbs? Why are opportunities so scant for others?

Don’t get me wrong. I am appreciative of the doors that were opened and of the people who looked out for me. This is why I am compelled to give back. Today, I am the board vice president of Reaching Out From Within, the organization that changed my life.

But until the system works this well for everyone, all of us, myself included, have a lot of work to do.

Jason Miles, Vice President, Board of Directors of Reaching Out From Within

Date

Friday, January 15, 2021 - 11:45am

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Override default banner image

Related issues

Criminal Legal Reform

Show related content

Pinned related content

The Stone Catchers

The Women Left Behind

The Founding Fathers have spoken, and they support Clemency

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Show PDF in viewer on page

Style

Standard with sidebar

Show list numbers

The law is clear: Every person charged with a crime in America has the right to effective counsel, but for two, Wyandotte County men, this unequivocal right rang hollow.

Lamonte McIntyre and Odell Coones were convicted of crimes and later released after serving a combined 30 years in prison. Both men were charged and convicted of murder, both men were sentenced to spend the rest of their lives in prison, both men were represented by the private attorney appointment defender system, and both men have said their attorneys failed to effectively defend them.

Their cases, and the misery they and others have endured, highlight the need for Wyandotte County to establish a public defender office. The reasons are clear. Lawyers in an established public defender office would have the advantage of practicing law in this sphere daily, they would have resources private practice lawyers simply do not have, and it would remove appearances of impropriety tied to the judicial appointment of lawyers and lawyers rushing through the process to receive payment.

Such an office would also help us meet our obligations handed down by the United States Supreme Court.

Here’s a quick history lesson. In Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the right to legal counsel, established in the federal courts by the sixth amendment, must be guaranteed in state courts. The Supreme Court held this right was guaranteed under the fourteenth amendment’s due process clause, of which “no state can deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” This Supreme Court case is the foundation upon which state public defender offices came into existence.

So, how would a public defender system differ from the current private attorney appointment defender system in Wyandotte County?

There are two forms of public defenders here in Kansas. Usually what comes to mind is a public defender or a “court-appointed attorney.” It is identical to a mid-size law firm or a small prosecutors office. They usually consist of a dozen lawyers, a few paralegals, assistants, and one or two criminal investigators. These public defender offices usually only take felony criminal cases. Most state public defender’s offices have existed since the early 80s and 90s. These offices typically have the greatest depth of knowledge and expertise in defending felony crimes. When these public defenders receive proper training and resources, they become the greatest advocates for the accused.

The Court is made aware of the individual’s indigent status and inability to hire a private attorney. The public defender’s (PD) office then dispatches one of its lawyers to court, to visit the individual in jail, to speak to and explain the process to him or her, and then to use all of their resources and collective experience in the office to defend their client’s constitutional rights.

In Kansas the PD’s office is funded by the State Board of Indigent Defense Services, which is separate and apart from the Court and prosecutor’s office. The Court simply assigns the case and has nothing further to do with the representation of the accused.

The second system is the “private appointment” public defender system. In Wyandotte County there is no public defender’s office. The Judges in Wyandotte County who preside over the criminal cases keep a list of private attorneys to appoint to the various cases. When a defendant is unable to retain counsel, the judge hearing the case chooses an attorney from their list. Each appointment list is comprised of multiple attorneys, all of which are in private practice and given permission by the local judge to be on the list. The attorneys vary in years of experience, office standards, and level of cases they have handled.

Most of them are in solo practice or have one or two other attorneys in their office. Many of these attorneys do not have paralegals, criminal investigators, and often, no assistants. When called upon by the Court to defend an individual of a crime, they do the best they can with the tools they have. I intimately understand this process, as I was at one point in my career on those lists. Having worked in a public defender’s office and was also appointed to represent criminal defendants while in private practice and now, as the District Attorney, I can say with absolute certainty that Wyandotte County needs to seriously explore establishing a public defender’s office.

A public defender’s office will provide continuity of criminal justice services for those who cannot afford an attorney. Public defenders have the luxury of being around others who are practicing the same type of law and have an exclusive process and expectation regarding the court process. There are currently dozens of private appointed defenders who operate by their own standards and practices. There is no administrative oversight and expectation for private, appointed defenders.

A PD office would remove the appearance of impropriety from the attorney selection process. I love that Wyandotte County judges are elected. Citizens of our county should decide every four years who serves as judge in our Courts. Our esteemed judges hold the massive responsibility of assuring justice is fairly and equitably executed. However, if an elected Judge appoints attorneys who have donated to their campaigns, to the community, that’s a troubling appearance of impropriety.

A PD office would also remove perverse incentives. When a private attorney is appointed to represent a client, they must wait until after a case is finished before they can receive payment. Although this may not be a subconscious motive for attorneys to plea cases and finish cases quickly, it has the potential for abuse. If a public defender’s office were put into place in Wyandotte County, hired attorneys would receive a steady paycheck and would not be lured into rushing to close cases in pursuit of payment.

Wyandotte County deserves to have a well-balanced, transparent, and public discussion regarding if a public defender’s office should be available in Wyandotte County. If we are to make the criminal justice system fair and just for everyone, we must provide every individual with effective competent counsel, without the taint or appearance of impropriety.

In all fairness, I also understand that public defender offices have their share of issues, but right now, they are the best solution that we have. It’s time to begin the discussion about the best option for criminal defendants receiving a fair and just defense.

I have not mentioned cost here but only because it needs and deserves further study. Little is known regarding the actual cost benefit analysis of a private defender system versus a public defender’s office. But taxpayers should be aware, however, if we are fostering a system which is substantially more expensive than other defender systems. As the fourth-largest county in the state, we have a fiscal responsibility to ensure we are prudently spending tax dollars while responsibly pursuing justice. An objective cost analysis should be undertaken to determine the value of our current system.

As a minister of justice, I am doing everything within my office’s power to not create anymore McIntyre or Coone cases which were miscarriages of justice. But if we are talking about cost, what possible price tag could we place on the decades of freedom they and others like them have lost?

They’ve already paid a price more costly than we can imagine and everyday we delay in establishing PD offices everywhere that doesn’t have them, those costs will continue to rise.

Mark A. Dupree, Sr., District Attorney of Wyandotte County, KS

Date

Thursday, December 10, 2020 - 4:00pm

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Override default banner image

Related issues

Criminal Legal Reform

Show related content

Pinned related content

The Stone Catchers

Clemency Q&A with Sharon Brett, Legal Director

The Clemency Project: Stomach, and now, liposarcoma cancer

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Show PDF in viewer on page

Style

Standard with sidebar

Show list numbers

Pages