My dear friend, Ted Ayres, after years of serving as vice president/general counsel for Wichita State University, now hosts an engaging show on KPTS in Wichita about one of his passions – books. Ted reads 150 to 200 books a year.

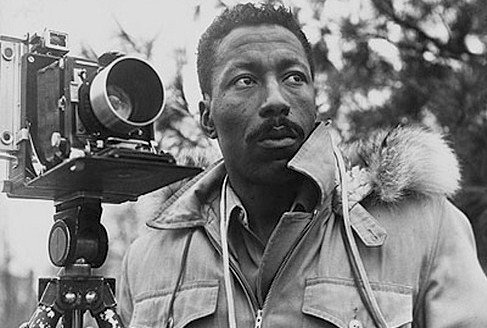

Ted and I worked together years ago, to help WSU secure Mr. Parks’ collected works, letters, record collection, etc. Under Ted’s leadership, WSU beat out the Library of Congress and the New York City Public Library system, which also vied for the collection.

We reminisced about an alternately celebratory but sobering moment he had introducing the renowned photographer, filmmaker, and author. A moment our state and our nation seem tightly locked inside.

As many people have done, Ted dipped into Mr. Parks’ oceans of work and pulled up the poem, “Kansas Land,” which spoke lyrically to the natural beauty here. It reads:

I would miss this Kansas land.

Wide prairie filled with green and cornstalk;

the flowering apple,

Tall elms beside glinting streams

...

Silver September rain, orange-red-brown Octobers and

white Decembers with hungry

smells of hams and pork butts curing in the

smokehouse.

Ted stopped there in the poem, as many people had done in the past.

So, Mr. Parks did what he usually did: he called Ted on it.

With the grace and calm he’d become famous for over the years, Mr. Parks pointed out how often people introducing him choose this poem and how equally often they omit the last stanza that reads:

Yes, all this I would miss--along with the fear,

hatred and violence

we blacks had suffered upon this beautiful land.

We laugh about it now but like Ted, I think this anecdote has a message for easily half of our nation.

We don’t live in a racial heaven or Hell, but those extremes do exist. We cannot, as many Americans continue to do, embrace our celebratory moments while denying many if not most of our darker chapters.

Just like with the poem, we must find ways to reconcile the truth of both – the beauty we see as well as the ugliness we choose not to see.

Professor, activist and now longshot-Presidential candidate Cornel West is fond of saying that we do not arrive at “Truth” with a capital “T,” until, “suffering is allowed to speak.” That kind of truth is the key ingredient for any kind of reconciliation.

Truth-telling, moves us forward. It’s the reckoning before the reconciliation. We’re going to have to get comfortable with the sharing of these painful but redemptive truths as we work to move beyond the current, uglier moment.

Date

Tuesday, February 6, 2024 - 3:00pm

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Related issues

Racial Justice

Show related content

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Show PDF in viewer on page

Style

Standard with sidebar

Show list numbers

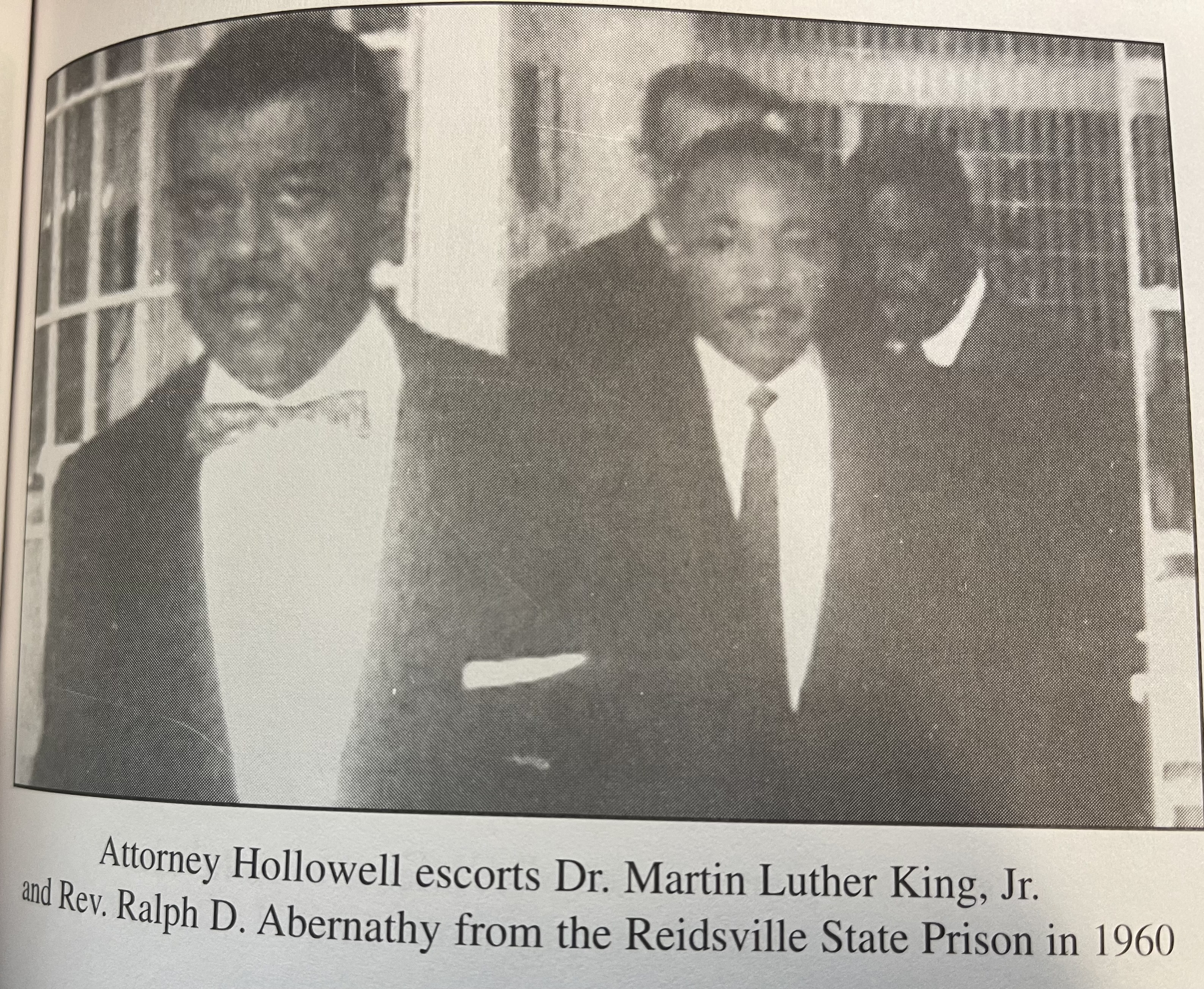

A John F. Kennedy documentary that aired recently referenced efforts to free the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. from a brutal Geogia prison back in 1960, but didn’t mention the man escorting King out of the facility, Lawyer Don Hollowell.

Coretta Scott King had requested help from the Kennedy’s to free her husband from a four-month, hard-labor sentence in Reidsville State Prison. King’s crime? Participating in a sit-in.

There was a lot of handwringing and talk about political courage in the Kennedy’s camp. They needed the Black vote to ascend to the presidency but at the same time, the candidate feared alienating white voters. We need Hollowell’s no nonsense courage today.

Hollowell, originally from Wichita, had been defending King against sit-in charges filed when King protested at an Atlanta department store. Prosecutors dropped those charges, but they subsequently charged King with violating probation and sent him to Reidsville in 1960.

King often found himself the target of prosecutorial power and the many creative ways prosecutors filed charges not necessarily because King had broken the law, but because King challenged racial norms. Prosecutors, then and now, wield enormous power.

Hollowell represented many civil rights icons including Julian Bond and John Lewis. Hollowell brought the case that got Journalist Charlayne Hunter Gault and classmate Hamilton Holmes who’d go on to become a doctor, admitted to the University of Georgia.

Hollowell regularly faced racist judges and juries in the darkest most dangerous reaches of rural Dixie and to the astonishment of many, managed to win more than his share of such cases. People used to prop ladders on the windows of old court houses to watch him work.

By 1964, with Hollowell seeking a judge seat in Fulton County Superior Court, it was King who gifted him some SCLC staffers to help his campaign, which was unsuccessful.

But under President Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration, Hollowell became the first Black man to lead the southeastern regional office for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which he directed from 1966 to 1976. Hollowell served as president of the Voter Education Project from 1971 to 1986 and was the recipient of countless awards, including the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund’s Lawyer of the Year (1965), and the Civil Liberties Award from the American Civil Liberties Union (1967). In 2002, he received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Georgia, the same university he had helped to desegregate 40 years earlier.

Hollowell died in 2004 but not before integrating Atlanta schools, colleges, and public transit.

At some point, we’ll need to stop living on his courage, and find our own. And real courage, not the political kind.

Date

Thursday, February 1, 2024 - 12:00pm

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Related issues

Racial Justice

Show related content

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Show PDF in viewer on page

Style

Standard with sidebar

Show list numbers

This editorial was originally published by the Wichita Eagle on December 23, 2023.

In 2017, Ricky Wirths walked into the offices leased by the Kansas Department of Revenue at a local strip mall, asked for the tax agent who’d recently seized his property, and open fired on the entire office, shooting the tax agent five times.

He then told an acquaintance that he’d “just killed a guy,” although he would prove to be incorrect — the victim miraculously survived.

Once apprehended, Wirths faced a $250,000 bail bond, which was later increased to $500,000.

This meant that after attempting to kill a state official, on state property, Wirths could post bail, go home, hire a lawyer, and begin building a defense for the attempted murder charges he was facing.

But recently, Sedgwick County prosecutors charged 16-year-old Makyh Townes with second-degree murder in what a friend termed an accidental shooting.

The 16-year-old had his bond set at $2 million and he’s sitting in an adult jail.

Wirths is white. Townes is Black.

The challenge here hinges not on the crimes (in this case, both are violent crimes), but on the capriciousness of the bond system as a whole.

The ACLU of Kansas believes the state could address these socially destabilizing and anti-democratic disparities by eliminating cash bail for non-violent offenses. Pretrial incarceration caused by unaffordable bail remains one of the greatest drivers of convictions and it exacerbates already ballooning jail and prison populations. In 2020, roughly 630,000 people were locked up in local jails. Most of them had not been convicted of a crime.

After an arrest — wrongful or not — a person’s ability to leave jail and return home to fight the charges typically depends on their access to money. On any given day, 5,000 people sit in Kansas jails not because they are guilty, but only because they can’t afford bail.

That’s because, in virtually all jurisdictions, courts require people pay cash bail to secure their freedom. Originally, bail was designed to compel people to return to court to face charges, but now we know that simple solutions like court reminders can achieve that purpose.

Townes’ mother said in a Wichita Beacon article that she worries about her 16-year-old son. He’s sitting in an adult jail, missing lots of school, and mourning his friend’s death. Even if acquitted, he’ll deal with this trauma perhaps for the rest of his life.

All because they didn’t have money for bail.

Poorer Americans and people of color often can’t afford to come up with money for bail, leaving them sitting in jail awaiting trial, sometimes for months or even years.

For those that do try to pay, bail amounts can be a significant hardship. They won’t ever get the money back regardless of the outcome of the case — even if the arrest was a case of mistaken identity and no charges were ever filed.

Across the country, bail reform has taken root and even gained support from within law enforcement and among judges and prosecutors. Judicial decision-makers who influence bond amounts have the ability and the power to correct our two-tier system of justice.

And according to survey research this year, 69% of Kansas voters support reforming cash bail to create a path for most people to go home the same day they’re arrested if they don’t pose a flight risk or a threat to others.

Kansans clearly believe release decision should be based on individual circumstances — not how much money someone has.

Date

Tuesday, January 23, 2024 - 5:30pm

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Show related content

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Show PDF in viewer on page

Style

Standard with sidebar

Show list numbers

Pages