Under the Kansas Constitution, women had limited voting rights. Women could vote in school elections.

But full suffrage for women here in Kansas took focused work from real visionaries.

We could use the leadership of Clarina Nichols, Susanna Madora Salter and Lucy B. Johnston even today, as extremists in the legislature continue their attacks on voting rights for everyone.

Nichols made her name as a journalist in the Quindaro settlement but was also an abolitionist and a suffragist. She was present at the Wyandotte Constitutional Convention of 1859 where she advocated for women’s property rights, equal guardianship of children, and “the right to vote on all school questions.”

Slater actually served as a mayor 25 years before women had state-level voting rights. She was mistakenly voted into office in Argonia in 1887, after men placed her name on the Prohibition Party ticket, “as a joke.”

Johnston served as president of the Kansas Equal Suffrage Association and the Kansas Federation of Women’s Clubs. She played a key role in the 1912 amendment that gave Kansas women the right to vote.

This is a short list. Many other Kansas women strategized and fought for the right to vote.

Sadly, this work must continue in the face of perpetual and persistent attacks on voting rights.

At the moment, there are seven bills pending in the Kansas legislature aimed at limiting early, in-person voting, placing additional restrictions on mail-in ballots, ending the three-day grace period for mail-in ballots and much more.

In their memory and for our future, we have to keep fighting.

Learn more about the women’s Suffrage Movement in Kansas at: The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Kansas | Blog | Museum of World Treasures

Date

Monday, March 4, 2024 - 4:30pm

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Show related content

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Show PDF in viewer on page

Style

Standard with sidebar

Show list numbers

Though his martyrdom lives on, justice has eluded the Rev. James Reeb.

A monument to his life stands in front of the Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, Ala., marking the day the Wichita native left his wife and children in Boston to attempt to march to Montgomery for voting rights and beaten to death with a club for his participation.

Despite the passage of decades and the official status of his death still ruled unsolved, we can yet deliver to the Unitarian Universalist minister the justice his life so importantly deserves.

Reeb had watched the Bloody Sunday attacks on peaceful civil rights marchers and then answered the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s national call for clergy to descend on Selma to make another attempt at marching to Montgomery.

But deciding at the last moment not to march into the teeth of a phalanx of law enforcement, King turned around and led marchers back to the church.

That evening, segregationists clubbed Reeb and two other clergy from out of state. Our tour guide said that because Reeb had marched for Black voting rights, the Selma hospital would not treat him. He died two days later from the beating. Dr. King gave the eulogy.

Then President Lyndon Johnson used Reeb’s martyrdom to pass the Voting Rights Act.

But in the decades since, extremists have targeted the Voting Rights Act for dismemberment, attacking key passages and weakening voting rights for wide swaths of the American electorate.

Aware of this and aware that one of Reeb’s accused killers ran a prominent used car lot in Selma, a group of us Kansas tourists toured the town extensively in “Justice for James Reeb” t-shirts.

But more than anything, Reeb likely cared more about the voting rights of others. He’d also more than likely approve of the work the ACLU of Kansas has undertaken in the spirit of voting rights. He chose the Unitarian church specifically because of its emphasis on social activism.

We could honor his memory by cementing certain voting rights measures that include expanding early voting, increasing accessibility (curbside voting, increasing the number of voting sites, and improving language access. We could also work harder to ensure that people with felonies know their voting rights.

So, what do you get the man who gave everything?

An honest fight for these measures would make for a great start.

Date

Tuesday, February 20, 2024 - 12:15pm

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Related issues

Racial Justice

Show related content

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Show PDF in viewer on page

Style

Standard with sidebar

Show list numbers

In the 2021 hybrid documentary/scripted feature based on Ibram X. Kendi’s award-winning book, Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas, Princeton Prof. Imani Perry connected several historical dots over the span of centuries.

“The response to Black progress in the country is punishment,” said Perry, who works at the Center for African American Studies at the Ivy League school.

History sides with Perry. Reconstruction begat roughly 100 years of segregation and lynching. Just 12 years after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s, death, the Reagan revolution tried to erase Civil Rights gains. President Obama gave way to extremism across the country.

But in that resilience, Black America set out seeking freedom, and agency and the bounty promised to any American daring to dream.

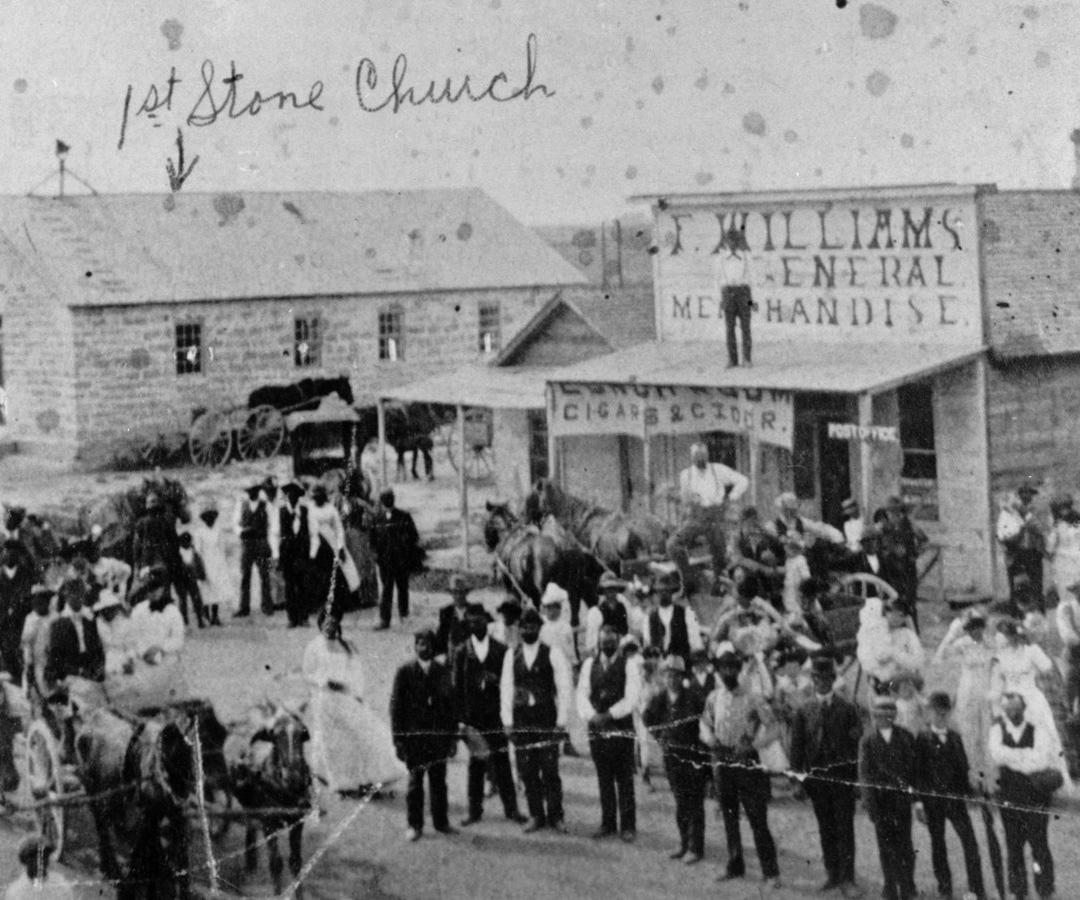

Nicodemus is a product of that resilience.

Formerly enslaved people left Kentucky just as Reconstruction began to crater, releasing a torrent of hatred in violence into the nation’s bloodstream. With terror on their heels and the promise of freedom ahead, thousands of the formerly enslaved hammered together wagons and headed West.

In 1877, a group of those settlers landed in Nicodemus on the high plains of northwest Kansas. Six Black men and one white man created the town company. By 1976, the nation had named Nicodemus a National Historic Landmark. It has survived, but barely. It has only a couple dozen residents anymore.

Still, its historical significance remains sprawling.

Some historians have claimed the name sprang from the biblical story of Nicodemus and Jesus’ declaration that we must be “born again.”

While poetic, that’s just not so, said Angela Bates, a Nicodemus native, the town’s historical protector, and founder of the original Kansas African American History Trail.

“Nicodemus is named for the African Prince mistakenly enslaved but who eventually purchased his freedom,” said Bates.

Bates said many of the town’s original progeny came from the unusual union of Former Vice President of the United States, Richard M. Johnson, and the woman he’d enslaved and married. That genealogy resounds. Despite surface racial differences we’ve turned into galaxies, we remain bound – ironically – by blood and soil.

Nowadays, former residents, Black history tourists and more return to Nicodemus annually to celebrate the town’s bright history, filled with a sense of pride of what the town once represented.

They’re connected to a past where terror played virtually every part and like the people who hurled themselves into the nation’s westward expansion, they’re still in search of that promised land, that promised freedom, that magical land that won’t punish them for flourishing.

Date

Wednesday, February 14, 2024 - 10:45am

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Related issues

Racial Justice

Show related content

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Show PDF in viewer on page

Style

Standard with sidebar

Show list numbers

Pages