(CN) — It's called the "Kansas Two-Step," but it's not a dance, at least in the literal sense.

It's a maneuver where the state trooper during a traffic stop turns away from the driver's door, and then turns around and starts talking to the motorist again, thus initiating what the Kansas Highway Patrol describes as a voluntary interaction with the trooper — as opposed to the rest of the traffic stop, which is involuntary.

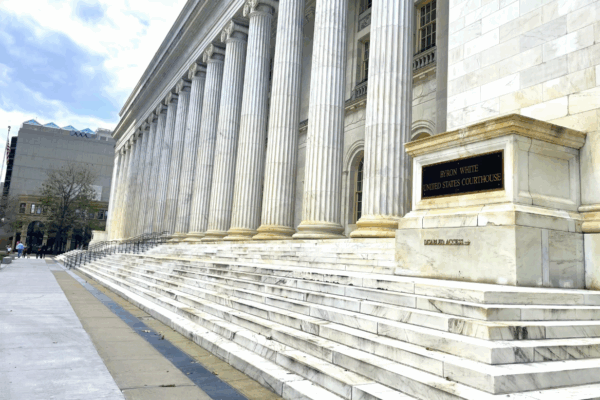

The future of the two-step is now in the hands of three 10th Circuit judges who heard attorneys for the ACLU and the state of Kansas argue Friday over how troopers implement the practice.

The state of Kansas appealed a 2023 order by Senior U.S. District Judge Kathryn H. Vratil where she ruled that Herman Jones, then superintendent of the Kansas Highway Patrol, was responsible for a practice that unlawfully detained motorists, particularly those from out of state, without reasonable suspicion or consent.

"[I]n the name of drug interdiction, the Kansas Highway Patrol (“KHP”) has waged war on motorists—especially out-of-state residents traveling between Colorado and Missouri on federal highway I-70 in Kansas," wrote Vratil, a George H.W. Bush appointee. "[T]he KHP does not routinely require or ensure that troopers follow the law with regard to reasonable suspicion and consent, and it has developed a practice of detaining motorists under circumstances which the Fourth Amendment forbids."

Vratil ruled that troopers must not take into account if a motorist is traveling to or from a "drug source" or "drug destination" state or along a drug corridor.

Civil liberties groups have criticized the two-step because motorists don't feel like they have the freedom to leave with a trooper standing next to their vehicle. The practice allows troopers to elicit information and buy time for a law enforcement officer to get to the scene with a police dog.

The case derives from two traffic stops that took place on Interstate 70 in Kansas, one in 2017 and one in 2018, though Vratil addressed other two-step cases in her ruling since the Erich case became a class action. In the 2017 case, a trooper pulled over brothers Blaine and Samuel Shaw of Oklahoma City in Hayes, Kansas, on their way to Denver to visit family and friends and detained them as their vehicle was searched. In the other case, a trooper pulled over Colorado residents Mark Erich and Shawna Maloney near Salina, Kansas, who were traveling to Alabama in a Winnebago.

The plaintiffs sued Jones, who at the time was the director of the Kansas Highway Patrol. He has since retired and was terminated as a defendant. But current superintendent Erik Smith was added as a defendant last year. The plaintiffs also sued the troopers who stopped them.

Sitting on Friday's panel were U.S. Circuit Judge Harris L. Hartz, a George W. Bush appointee, U.S. Circuit Judge Paul Joseph Kelly Jr., a George H.W. Bush appointee, and U.S. Circuit Judge Richard Edward Neel Federico, a Joe Biden appointee.

Dwight Carswell of the Kansas Attorney General's Office argued that Vratil's instructions to the Kansas Highway Patrol in her order conflicted with Supreme Court precedent, but most of his arguments centered on the claim that the plaintiffs lacked standing. The likelihood of the plaintiffs being stopped again in Kansas and a trooper having reasonable suspicion to detain them is very low, he said.

“Plaintiffs’ fears of a future Constitutional violation are purely speculative," he said. “There is no KHP policy of detaining motorists without reasonable suspicion ... Even if a KHP trooper is disproportionately stopping out of state drivers for speeding, for instance, that doesn't violate the Fourth Amendment if they are actually speeding."

Kunyu L. Ching of the ACLU of Kansas argued for the plaintiffs and appellees and cited the court's 2016 Vasques v. Lewis decision that said traveling to or from a state with legalized marijuana is meaningless when calculating reasonable suspicion.

"Despite this courts directive that reliance on such factors is wholly improper, the undisputed testimony from KHP employees, from top to bottom, shows that the KHP deliberately ignored Vasques for years," Ching told the judges. "There was no change in policy or practice until appellees filed this lawsuit. Instead, the KHP continued with business as usual."

"Taking appellants to their arguments' logical conclusion, no one ever has standing to to challenge a traffic stop or subsequent detention under the Fourth Amendment, and federal courts can never enjoin a state law enforcement agency to correct unconstitutional failings, and that simply cannot be," Ching said.

Carswell said that the Vasques case was part of Kansas Highway Patrol Training. "It was only the practice that the district court found lacking, not the official training."

Both attorneys faced questioning from the panel. But it seemed more detailed for Ching.

The judges did not indicate when they would rule on the matter.